Walking is by far the most common and accessible physical activity known to humans. Its USP is its inherent simplicity. But things are not so simple in today’s increasingly tech-driven world: for example, we carry along some or the other device we are surrounded by (and which are so much a part of our existence) even when we step out for barely five minutes. Mindful walking, focused fully on the activity, is rare.

READ MORE :

Why a punching bag may not be a good idea

Dance to a classical fitness mantra

Mass destruction: the ills of steroid abuse

The modern desire to multitask too has seeped into walking. However, the human brain knows no such thing as multitasking, and is instead known to switch from one task to another, and back to the first task, quickly (what is known as dual task performance or task switching). So, multitasking could take a toll on one’s mind.

Practising mindfulness, paying full attention and being in the moment, on the other hand, is known to decrease stress levels.

“Mindfulness encourages one to pay full attention to moment-by-moment experience, rather than becoming caught in worry or rumination,” according to a research article published in 2021. “This reduces amygdala activation, thereby reducing overall levels of stress.” Amygdala is a region in the brain known for processing psychological stressors and coordinating physiological stress responses.

Mindfulness exercise

Mindfulness entails performing a given task in a truly conscious manner, with undivided attention on the activity. Divya Thampi, a productivity coach based in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, says mindfulness is about “being present in the moment, fully and without judgement”.

“Studies show that what differentiates people who perform at peak levels [in any area of life] from others is that they do a lot of practice alone, and mindfully (a specific type of practice called purposeful practice),” says Thampi.

One way to practise mindfulness is to weave it into one’s daily life, in each small or big task. And what better way to start a new healthy practice than to stack it on to another healthy practice – exercise! Known as habit stacking, this is an effective productivity technique for honing new habits.

In ‘Aligning Mind and Body: Exploring the Disciplines of Mindful Exercise, an article published in ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal in 2005, Dr Ralph La Forge, physiologist and managing director, Duke Lipid Disorder and Disease Management Training Program at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, says, “Mindful exercise generally relies on self-monitoring of perceived effort, breathing, [proprioception or muscle sense] and non-judgmental self-awareness, rather than cueing entirely on an exercise leader or peer-influence, as is most often experienced in conventional group exercise classes. It can be readily executed at low-to-moderate exercise intensities and is adaptable to a wide range of functional capacities.”

Mindfulness is an innate human quality, but training the mind and body to access that mindful state can help hone it further.

Giving the example of long-distance runners, Thampi says, “Running distances such as 10km or 20km can get painful at times. So, the tendency is to distract oneself by running with friends or with music on, which help take one’s mind away from the pain and clock in the miles.”

However, mindful running helps push the performance envelope.

“The peak performers or the best runners are the ones who run alone and run mindfully, paying attention to their body and form,” says Thampi. “They check whether their shoulders are slumping, or whether and where exactly in their body they are feeling an ache or pain. They are mindful about what shift they can bring about in the angle of the ankle or the knee, or the way their strides are landing on the ground, etc. to run better, thus performing efficiently.”

Tai Chi, hatha yoga and qigong are some of the oldest, most classical forms of mindful exercise. Contemporary forms include NIA, Chi ball, meditation walking, yogarobics, yogilates, Chi Running, Aqua Tai Chi, Yo Chi, Flow Motion, mind-body circuit exercise, and many ethnic dance routines.

Walking meditation

Among all forms of mindful exercise, meditative walking has an upper hand given that it does not require any special physical skill or training. The concept of mindful walking is known to have Buddhist origins.

“Spaces have a way of confining you,” says Thampi. “But when you are walking [outdoors], you get out of those confinements. And emotion is energy in motion. When you are sitting without movement, your emotions can start going in a certain direction and it can get intense and not so pleasant. Your emotions do not have any release. But when you start walking, that energy gets used up and [is] thus released. Your body also starts releasing the endorphins or feel-good hormones.”

Minding the body

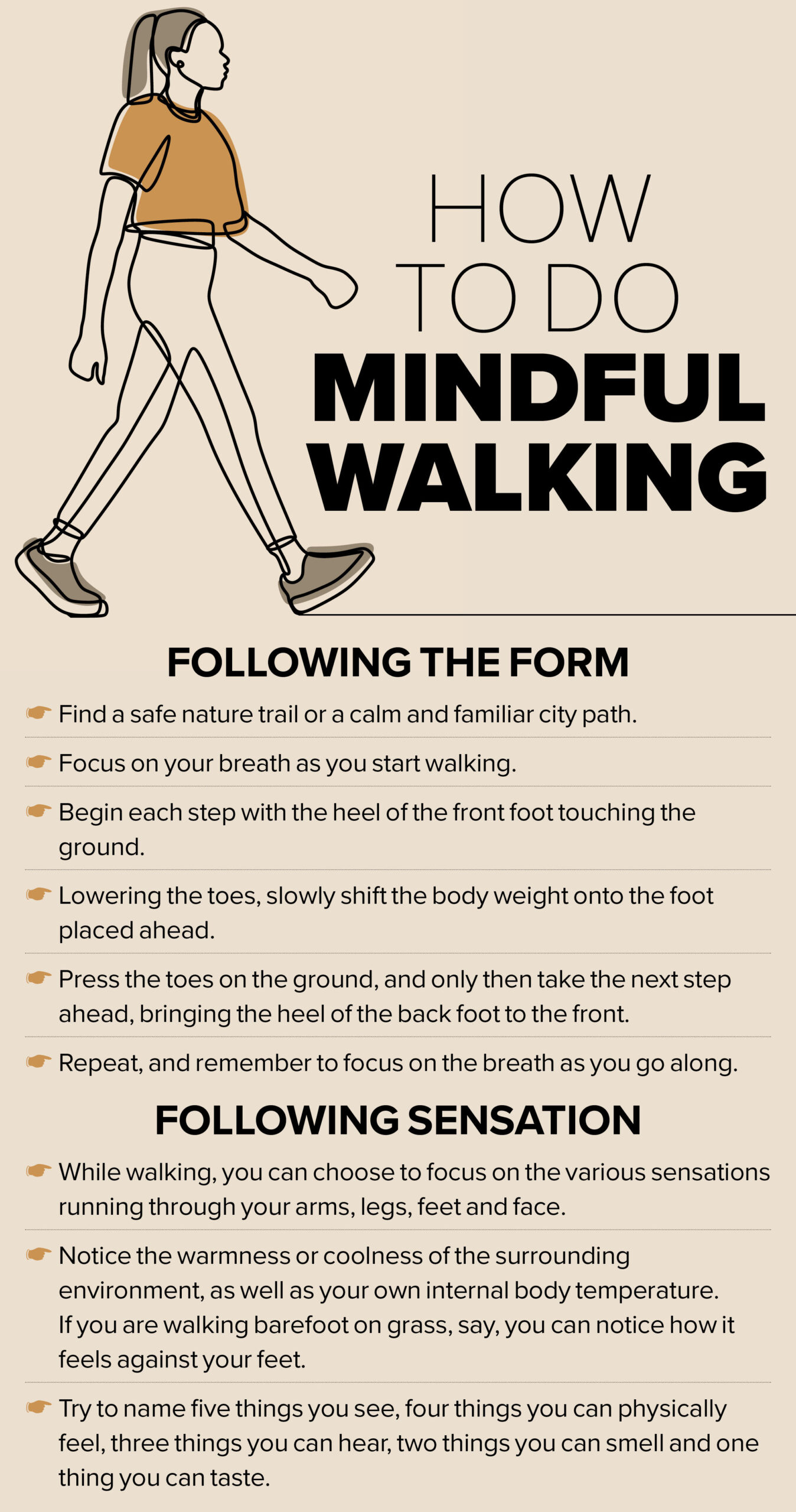

Thampi says that if a person focuses on the body while walking, they will have a better posture and form. If they pay attention to the breath, it gets better regulated, which helps regulate the heart rate. It all leads to increased efficiency, while listening to the body helps avoid overexertion or injuries.

“Mindful walking helps us to connect back with every aspect of our body: how our feet are landing, how our body is feeling, etc — which we otherwise do not pay attention to and take for granted in our day-to-day lives,” Thampi says. “It can even serve as a little mindful prayer, wherein one pays attention to one’s hands, feet, breath, etc. It’s meditative, like body scan meditation, and gives you an opportunity to observe one’s body and thank each part, thereby generating a lot of positive energy.”

Paying attention to one’s surroundings can be another way to connect with nature.

Nature walk

“Research conducted in transcontinental Japan and China points to a plethora of positive health benefits for the human physiological and psychological systems associated with the practice of shinrin yoku, also known as forest bathing, a traditional Japanese practice of immersing oneself in nature by mindfully using all five senses,” according to a meta-review published in 2017.

“The therapeutic effects of being mindful in nature include an improved immune system function (increase in natural killer cells/cancer prevention), cardiovascular system (hypertension/coronary artery disease), the respiratory system (allergies and respiratory disease), depression and anxiety (mood disorders and stress), mental relaxation (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) and human feelings of “awe” (increase in gratitude and selflessness).”

One can choose to focus on the breath, or the sensations that arise in the body or from the environment in which one performs the task. These could be the senses of smell, sight (colours, objects, flora-fauna, etc), taste, touch, temperature, the breeze, or the different sounds that one hears. “The key being not to attach oneself with anything and being a neutral observer to the changing scenes,” says Thampi.

Thus, the physiological and psychological benefits of walking, together with the healing touch of nature, make mindful walking ideal to declutter, cut digital noise and score some quality me-time.

Takeaways:

- Mindfulness is being present in the moment, fully and without judgement.

- Practising mindfulness decreases stress levels, while multitasking increases it.

- Walking in nature and focusing on different senses can be a therapeutic and meditative experience.