For the second day in a row Chandan Singh, 30, is running a low-grade fever. The Jharkhand-based businessman visits a pharmacy nearby and buys himself a course of antibiotics. Three doses bring the fever down but Singh must now contend with diarrhoea.

Like many of us, Singh shrugs off loose stools as a common side effect of consuming antibiotics. Little does he know that his unregulated use of antibiotics can increase the chances of his developing lifestyle disorders such as obesity and diabetes.

For some time now, scientists have had an inkling that antibiotics abuse may increase the risk of developing diabetes or other lifestyle disorders. Data has largely been consistent on this, but only recently have we begun to understand why and how this might happen.

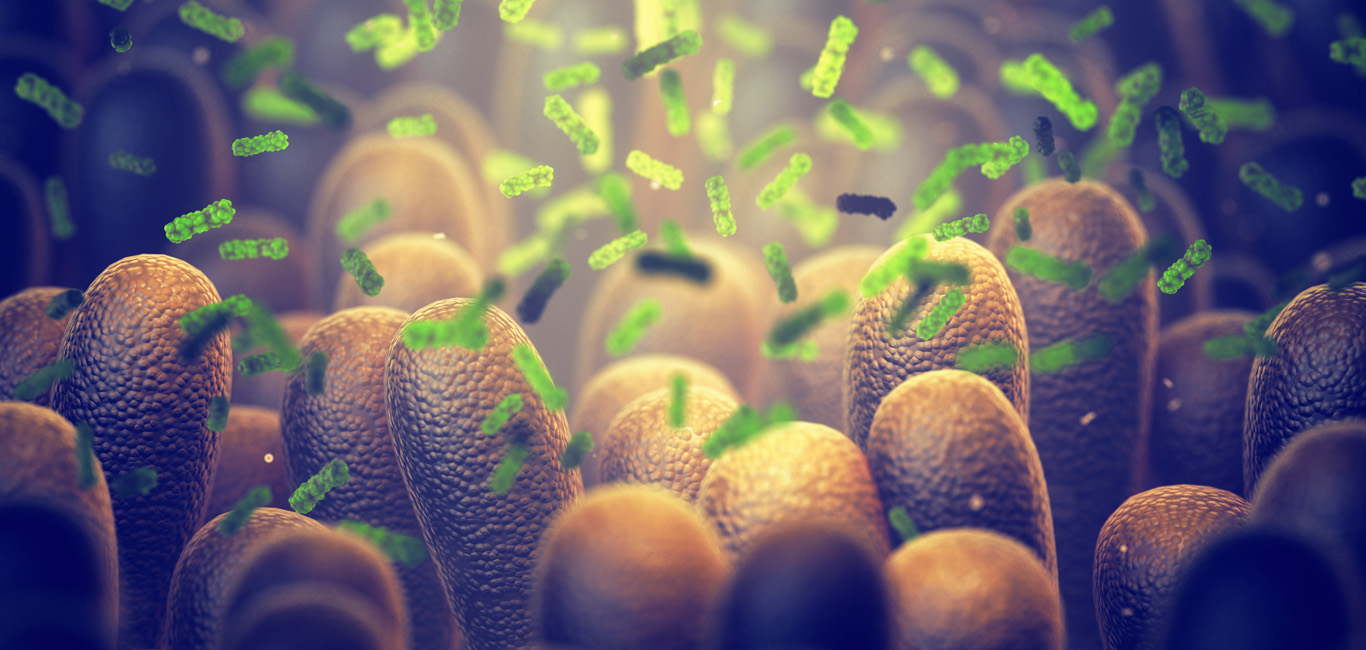

Antibiotics, scientists say, cannot differentiate between good and bad bacteria in our gut. They kill the friendly ones that are normally responsible for maintaining a healthy stomach and intestines. This is why Singh experienced diarrhoea. The long-term ramifications could be far worse.

Impact on gut microbiota

The gut microbiota – the good bacteria that colonise our intestines – does several important things. It helps to metabolise fatty acids and vitamins, aids in the absorption of micronutrients and the breakdown of amino acids.

Scientists have also found that it produces defensive antibodies for enhanced immunity, improved mental health, and for maintaining a healthy gut lining.

However, doctors and researchers worldwide are coming to a view that an imbalanced gut microbiome (also called gut dysbiosis) alters these functions, and that this is in turn linked with diabetes and several other diseases.

And the misuse of antibiotics, they believe, could be one of the major causes for this.

A close link is found

In a 2021 study, researchers from the departments of biomedical science and family medicine at the Seoul National University found a direct association between the number of doses and classes of antibiotics prescribed, and the incidence of diabetes.

Analysing data of over 200,000 Korean individuals, the researchers found that those who used antibiotics for 90 or more days had a higher risk of developing diabetes. Those who had used five or more classes of antibiotics were also at a higher risk of diabetes than those who had used fewer antibiotic classes.

“The clear dose-dependent association between antibiotics and diabetes incidence supports the judicious use of antibiotics,” the researchers wrote in the paper that appeared in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal.

Altering food metabolism

Another study done by researchers in the US and Romania said there was significant evidence to suggest that gut dysbiosis was a contributor to the development of “obesity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia”. The researchers proposed that antibiotics that alter the food metabolism process in the intestine could be a cause of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance.

Others have put out the hypothesis that antibiotics modify the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by microbes in the gut, some of which are essential in regulating insulin secretion.

Scientists have seen signs of this for a long time, with the gut microbiota of diabetic populations being distinctly different from those of healthy individuals. This implies that the gut microbiome could be an important participant in the progression of Type-2 diabetes mellitus, says Dr Abhimanyu Parashar, a clinical literature review specialist at Alcon in Bengaluru.

“The (dysbiosis of) gut microbiota is involved in obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation which are related to the development of Type-2 diabetes mellitus,” Dr Parashar adds.

Also read: A gut-derived protein could yield diabetes therapy

Why antibiotics wreak havoc on the gut

It has been well established that unprescribed, over the counter and incomplete use of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance, that is, the illness-causing organism becomes immune to the action of the antibiotic that was used.

An unintended consequence of this is that good gut microbes, which are not immune to these antibiotics, change their genetic material to prevent themselves from being killed. Scientists have found that this can lead to good bacteria going bad.

This is only natural, according to Dr Randhir Singh Dahiya, a professor of pharmacology at the Central University of Punjab. “Survival of the fittest is the law of nature. Only if they (gut microbes) develop resistance to antibiotics can they survive,” he adds.

How to save gut health

Both Dr Dahiya and Parashar prescribe judicious use of antibiotics to maintain a healthy gut and body. This along with other dietary and hygiene practices can significantly reduce the negative effects of antibiotics on an individual.

Here are a few simple steps one can follow to maintain a healthy gut while taking antibiotics:

- Use only the antibiotics prescribed by a doctor and never self-medicate.

- Complete the entire course of prescribed antibiotics.

- Ask your doctor to start you off with a lower dose of antibiotics and increase it gradually.

- Ask your doctor to test for the specific illness-causing organism and prescribe a narrow-spectrum antibiotic.

- Eat a lot of food containing probiotics such as curd, yoghurt, and fermented foods.

- Depending on the strength of the antibiotic, ask your doctor for a probiotic supplement.

- Try to consume antibiotic-free meat products.