Finding a one-size-fits-all solution to neurological disorders has confronted scientists for a long time.

At first, they peered at the faults in the nerve cells for an answer. However, they saw that playing with these primary drivers of every action and thought was riddled with several hurdles: the blood-brain barrier made them extremely hard to reach. Also, fiddling with neurons is tricky as they are delicate and prone to damage.

Another approach that gradually emerged was to look at neurological disorders as a kind of inflammation. As is known, the immune system has molecular sentinels that protect us from infections and clears out any toxin via inflammation.

Scientists earlier considered that the brain worked as a separate entity from the immune system.

“In the past, the immune system was considered to be aloof from the brain and vice versa,” Dr Michal Schwartz, professor of neuro-immunology and a pioneer of the field at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, tells Happiest Health.

Intertwined roles

However, research advances over the past 15 years have found that the two entities are not alienated from each other. “Now we understand that these two systems work together, influence each other, and cannot live without each other,” says Prof Schwartz.

This approach opened a new line of thought for scientists – namely to explore treating neurological conditions through the immune system, which could potentially overcome the previous hurdles posed by the blood-brain barrier.

A tango of two

“The crosstalk between the brain and the immune system is essential in everything from neurodevelopmental to neurodegenerative [disorders,]” says Prof Schwartz.

According to recent studies, mishaps in the immune system, like a cytokine storm or the surge of immune chemicals, could affect how neurons function, according to recent studies. For example, impaired B-cells found in the body’s immune system could lead to a child developing autism spectrum disorders.

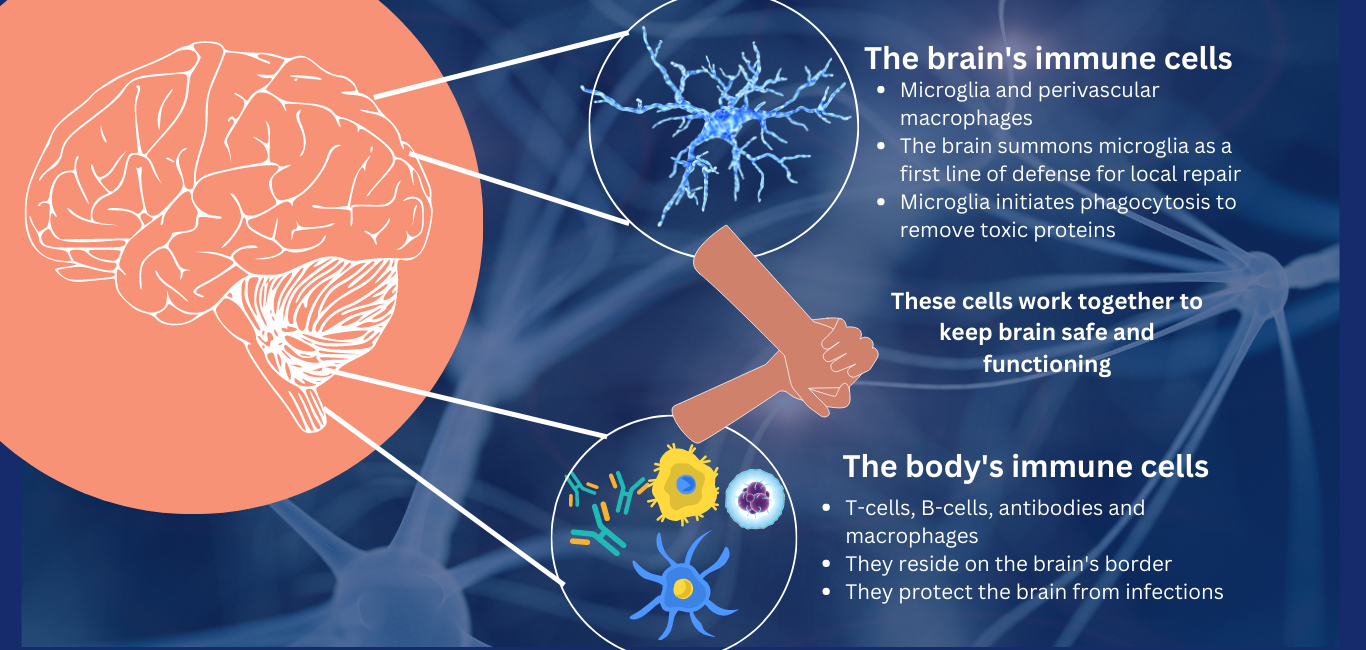

A later finding is that the brain has specialised immune cells apart from neurons; and they work in tandem with the body’s immune cells to keep the brain safe and sound throughout its lifespan.

At the same time, the brain’s immune cells also play a role in developing neurological disorders. For example, cells called microglia are the housekeeping agents in the brain that help to remove damaged and unwanted protein build-up (plaque) through phagocytosis. Studies have found that a skewed activity of these microglia could lead to Alzheimer’s disease.

Read more: Study reveals how nerve cells recruit brain’s immune cells to repair their damaged DNA

Further investigations have found that the body’s immune system has stationed some of its sentinels, like T-cells and B-cells, at the brain’s border to work hand in hand with the brain’s local immune cells.

A tiff can spoil the bliss

A harmonious communication between these two defence systems is essential for the healthy functioning of the brain. Any disruption in this interaction could lead to autoimmune neurological disorders like myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Read more: Oh so tired! The enigma of myasthenia gravis

Moreover, feuds between the brain and the immune system may manifest as mood variations and neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, Prof Schwartz says that the ability to cope with mental stress in post-traumatic events relies heavily on immunity. “In the case of immune-compromised individuals, the likelihood to develop post-traumatic stress disorder increases,” she adds.

Dr John Lukens, a senior researcher from the University of Virginia, USA, emphasises the importance of the crosstalk between the brain and the immune system in social disorders.

“If you think about it, we feel crummy, tired, or angry when we fall sick. It is really the immune molecules and how they interact with the brain that are dictating those feelings and behaviours,” he says. Erratic levels of cytokines and, in some cases, immune cells, he says, are seen during depression and generalised anxiety disorders.

A supporting network

Researchers have also found that several molecules are vital in keeping the microglia in top shape. For example, a 2022 study from Dr Lukens’ lab uncovered a molecule called SYK, which boosted the ability of microglia to remove amyloid beta. This neurotoxic protein compound is a culprit behind Alzheimer’s.

“We’ve also shown that it helps remove damaged myelin, [a protective sheath on the neurons], which builds up in the brains of people with multiple sclerosis,” says Dr Lukens.

Another study from the Washington University School of Medicine, USA, found that activating specific cells in the body’s fluid drainage system clears out the toxic protein build-up seen in Alzheimer’s. However, if damaged, these cells, called macrophages, may not be able to clear out the toxic amyloid protein.

Read more: Brain immune cells could hold the potential to treat Alzheimer’s: study

Touching both worlds

Scientists are leveraging this crosstalk and playing around with the immune system to tackle neurological disorders.

Many neurodegenerative disorders have inflammatory components which are triggered by an autoimmune response (the body’s immune system attacks its nerves) to them, says Dr Sudheer Kannoth, an autoimmune neurologist from Amritha Hospital, Kochi.

“We have come across a few people with Parkinson’s whose condition was caused by autoimmunity. In these cases, we prescribe medicine to modulate their immune system,” he adds.

Prof Schwartz also agrees that enhancing the immune system could be an effective way to tackle Alzheimer’s. “It will not only get rid of plaques but will also reduce overall inflammation. So in a single therapy, you overcome multiple factors contributing to disease,” she says.

Dr Lukens is hopeful that looking deep into these interactions could answer many of the mysteries of the nervous system. “Now, everybody agrees that the immune system is a major player, and may be in another 15 years, we’ll start seeing better immunomodulatory medicines for neurological diseases,” he exclaims.