Have you stood for too long and felt you were fainting? Not to worry. Around 40 per cent of people experience fainting spells or syncope once in their lifetime. In most cases fainting does not indicate anything serious.

However, in instances of pregnancy, low blood pressure or major cardiovascular conditions, fainting can pose damaging consequences.

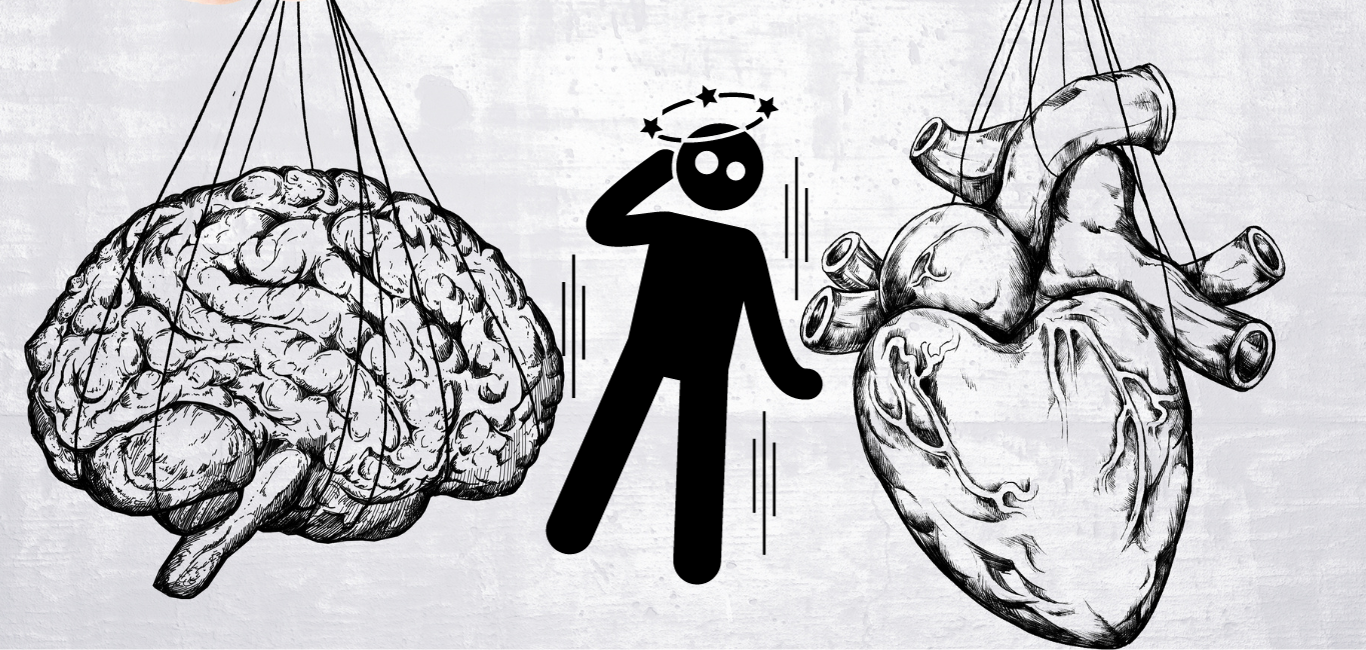

But what exactly causes fainting? Researchers from the University of California – San Diego, USA, may have just found a possible, more genetically defined, answer to it in the vagus sensory neurons. This answer also reveals a two-way link between the brain and the heart.

“We found that the heart and the brain do not work in isolation, but in unison,” says Vineet Augustine, assistant professor at the Department of Neurobiology, University of California and the senior author of the paper. He tells Happiest Health that while it is true that the brain sends signals to the heart to perform its function, the heart also signals the brain to work in tandem.

Fainting reflexes

In their study published in the journal Nature, the researchers analysed the science of fainting by understanding reflexes. These are automatic or involuntary responses of the body to an external stimulator. They integrate many processes happening within the body and are extremely crucial for survival by maintaining balance.

One such reflex of the heart is the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Prof Augustine explains that science has often debated the role of this reflex in fainting. He says that this automatic response happens when there is not enough blood flow to the heart.

“If the heart does not fill up with blood properly and it contracts, it probably triggers the Bezold-Jarisch reflex and causes fainting,” he says. The specific trait of this reflex is a reduction in heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing.

The nerve to faint

He and many scientists speculate that a particular cranial nerve – the vagus sensory neuron – also triggers this reflex.

Sensory nerves carry information from various parts of the body to the brain. One type of vagal sensory neuron has a protein called NPY2R on its surface. One end of these neurons has claw-like projections over the heart’s ventricles. The other end connects to the part of the brain stem involved in movement.

Prof Augustine and his team set out to confirm the role that vagus sensory neurons play in the fainting reflex. Upon specifically triggering these neurons in mice using flashes of light, the researchers saw that the mice that were moving about immediately fainted.

When these vagal sensory neurons were activated, the pupils of the mice dilated and showed the classic ‘eye roll’ that is characteristic of human fainting.

The mice also had reduced heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate. Imaging studies also found that the blood flow to the brain also reduced during the fainting spells. Once the light was switched off, the mice went back to moving around normally.

Genetic circuit

Not only did this study establish that the Bezold-Jarisch reflex does cause fainting, but it also found that a genetically defined circuit between the brain and the heart is involved when someone passes out, says Prof Augustine.

Apart from being able to find targets to prevent fainting, Prof Augustine hopes that this study cements the necessary knowledge about how the brain and the heart communicate with each other. “This could help in treating disorders that involve both the heart and the brain with a multidisciplinary approach,” he says.

Link to study: Vagal sensory neurons mediate the Bezold–Jarisch reflex and induce syncope