The gut, often dubbed the body’s “second brain,” can exert significant influence over the health of the actual brain. The extent of the gut-brain link has been especially evident in the case of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) — a condition whose cause and prognosis remain elusive in many aspects.

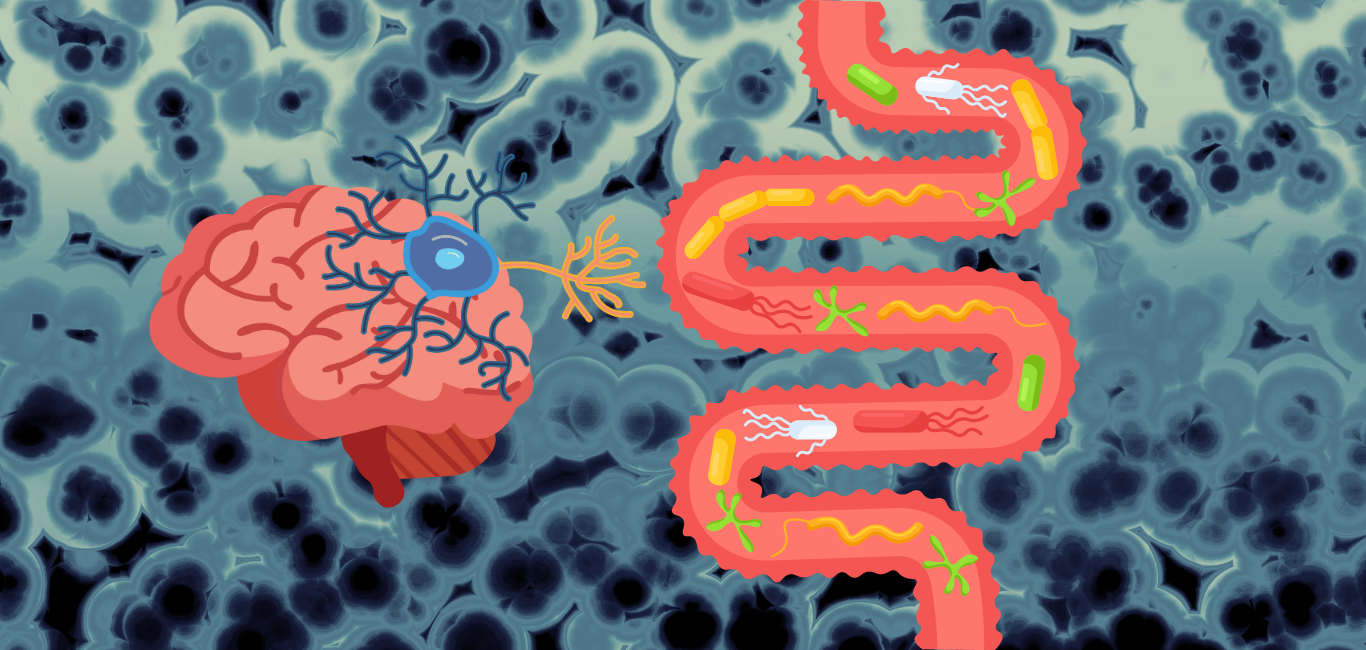

Scientists have for a while suspected a gut role in Alzheimer’s — those with the condition have specific alterations in their gut microbiota, and mice who have been given gut bacteria from humans with AD can end up developing the neurodegenerative condition themselves.

Now, a new study has added to our understanding of the gut-Alzheimer’s link, by transferring AD from humans to healthy young mice using a faecal-transplant. The mice went on to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms, including memory impairments linked with low growth of certain nerve cells in the hippocampus.

“We saw that animals with gut bacteria from people with Alzheimer’s produced fewer new nerve cells and had impaired memory,” noted Professor Yvonne Nolan, the study’s corresponding author, in a release.

The findings shed light on more possible mechanisms interlinking Alzheimer’s and our gut microbiota. Significantly, it establishes a causal link between certain gut microbiota and the development of Alzheimer’s.

“This study represents an important step forward in our understanding of the disease, confirming that the make-up of our gut microbiota has a causal role in the development of the disease,” said Professor Sandrine Thuret, Professor of Neuroscience at King’s College London and one of the study’s senior authors, in a release.

The research points to the importance of further studying the gut microbiome as a focus area for Alzheimer’s research.

The gut in our brains

It has been well established that the gut and brain have a bi-directional link, with our gut microbes implicated in everything from our physical to our mental and digestive health.

Establishing causality, however, has been tricky. For one, the exact range of mechanisms by which gut microbes influence overall health remains to be studied. The gut, as a processing hub for the food we eat, serves as a factory for the body. It makes true the adage that we are what we eat.

The hormones and neurotransmitters produced in the gut can travel across the body — over 90 per cent of our serotonin is sourced from the gut, potentially leaving the key to happiness with the microorganisms within us.

When it comes to Alzheimer’s, the link could be more complex. Alzheimer’s is characterised by the accumulation of abnormal clumps of protein called amyloid plaques and tangled fibres known as neurofibrillary or tau tangles in the brain.

Also read: Five stages of Alzheimer’s disease

The known gut-Alzheimer’s link so far has been multi-modal. It is known, for example, that gut bacteria can affect tau angles, altering the levels of a gene, APOE4, believed linked with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s.

In the case of the 16 mice that were given faecal transplants from humans with Alzheimer’s, the changes in their gut makeup correlated with known changes in human guts after Alzheimer’s.

When studying the rats gut bacterial composition 10-59 days after the transplant, there found higher numbers of strains that were also known to be elevated in the guts of humans with Alzheimer’s. Inversely, bacteria that produce butyrate, which can reduce the amyloid concentration in the brain that characterises AD, were also found in reduced numbers.

Cognitively, the effects were also clear. 10 days after the transplant, the mice were given behavioural tests designed to test their ability to grow new nerve cells when forming new memories. The results suggested that their hippocampal neurogenesis had already been affected. In simple terms, their brain plasticity and ability to generate new neurons had been compromised, as is the case with those with Alzheimer’s. All this, from a faecal microbiota transplant.

Catching Alzheimer’s early

This drop correlates with some of the symptoms seen during the early stages of Alzheimer’s. However, significantly, Alzheimer’s remains difficult to diagnose in its early stage.

The establishment of clear gut-based biomarkers for the condition could be a game-changer for early diagnosis and hopefully even treatments for the condition.

“People with Alzheimer’s are typically diagnosed at or after the onset of cognitive symptoms, which may be too late, at least for current therapeutic approaches,” noted Dr Nolan.

“Understanding the role of gut microbes during prodromal – or early stage- dementia – before the potential onset of symptoms may open avenues for new therapy development or even individualized intervention,” she added.

The results suggest gut dysbiosis could play a causal role in the progression of Alzheimer’s, with neurogenesis as a key mediator. More research is warranted to understand these pathways and their potential as targets for preventing or treating Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was a collaboration between APC Microbiome and the Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience at University College Cork (UCC), King’s College London and Dr Annamaria Cattaneo IRCCS Fatebenefratelli, Italy.